Christina Zendt’s Journal

Tulane University, New Orleans, LA

Table of Contents

Rembrandt, Shakespeare and Interiority

This seminar was so beneficial to me because of the diversity of creative talents paired with the open-minded approach to the program. By addressing everyone as equals rather than experts, in both artistic and academic spaces, the program made me able to see more openly from numerous perspectives. The validity given to everything we created—both in words and art—has enabled me to express myself with greater clarity and honesty. Before this experience, the strong connection I felt towards studying art made me most afraid of creating art. I was afraid that my paintings would be so bad that whenever I looked at great paintings my inability to create would distract me from appreciating them. But after this month of diverse experiences and exploration, I understand it is a process and I want to continue to try harder at making my own art alongside studying the history and the context of my predecessors.

This seminar was so beneficial to me because of the diversity of creative talents paired with the open-minded approach to the program. By addressing everyone as equals rather than experts, in both artistic and academic spaces, the program made me able to see more openly from numerous perspectives. The validity given to everything we created—both in words and art—has enabled me to express myself with greater clarity and honesty. Before this experience, the strong connection I felt towards studying art made me most afraid of creating art. I was afraid that my paintings would be so bad that whenever I looked at great paintings my inability to create would distract me from appreciating them. But after this month of diverse experiences and exploration, I understand it is a process and I want to continue to try harder at making my own art alongside studying the history and the context of my predecessors.

I felt empowered by the connectedness of everything in the program. Beginning each morning looking at a sonnet and thinking about how it appears visually, allowed me to comprehend a whole new approach to words. Thinking of things in terms of words and paintings makes great sense to me and allows the world to become so much more approachable. Now, with everything that I look at, I immediately think about how I would paint or describe it. This makes what I am looking at so much more tangible and it is easier to understand how it relates to everything else around it.

I am proud of what I have put into this journal to the extent that it is just the beginning. As I continue to develop my confidence with these new tools—paint, words, wax and Plastilina—I feel as though the energy of my thoughts and ideas is no longer stuck inside. Now I see how I can use that energy to express my thoughts and ideas through the different media, share them with others, and wrestle with their broader meaning. After all, Rembrandt and Shakespeare’s involvement with this search is what has allowed audiences to continue to be captivated with their works some 400 years later.

One

From the start of this trip I have been so intimidated by the prospect of articulating my perceptions of what I have seen and experienced in order to produce a journal. It wasn’t until this moment of sitting in the hills in Stratford that I got it; if I step back from attempting to express concise definitions of my experience and instead let it flow out of me, then my thoughts and senses will envelop themselves around my words and my pictures more clearly.

I have a fear that once I put something down on paper, (or canvas or Plastelina), that I have defined it. Once I label my feelings with such specificity, then someone will see or read it and interpret it differently than how I meant it. There is no one definition of me. I soak everything up like a sponge, constantly changing me. But, maybe, if I am patient enough to let myself seep out in a different way than I intended, then what I experience could actually mean something to someone else. Lear expresses his interior emotions with the most clarity when he lets go of words and reverts to animal noises, “Howl, howl, howl, howl!(5.3.255)” Lear’s emotion is brought forth by these sounds with such clarity because he is expressing his feeling rather than defining it. A howl is infinitely more powerful than a, “Gosh darn it, I’m so upset that Cordelia is dead.”

As Martha expressed in one of our discussions, the problem with words seems to be that they have agreed upon meanings, which allow them the risk of being boring and limited. But, in fact, we define words by their context, allowing innumerable meanings to be given to them. This is like paint, as well, with each individual stroke defined by its color, but when we see it in relation to the different colors that surround it, it adapts and changes to our eye, creating more possibilities for different perceptions. One new stroke affects everything else already on the page, as well as the page itself. That is why it is so important that the strokes work together to create the whole painting, for even the value of the page is effected by the presence of other values, and it can fool the eye.

An art history professor of mine in Savannah, whose wife was a photographer, once said that he understood art but couldn’t create it, while his wife could create art but not understand it. This had always irked me, and now I understand how he was mistaken. His wife understood art as well as he did, but she did not express her understanding in words as he did, but through her art. He didn’t see that they both understood, but expressed their understanding through different media.

My senses perceived everything with such clarity when I was running across the beach at The Hague, and they pulsated within me. It was after having spent the morning looking at some of my favorite paintings: Rembrandt’s Andromeda, Homer, and Susanna. My eyes were alive, and it was almost as if the rest of my body could not keep up with them, as they ran ahead of me to absorb every potent detail they came across. My nostrils were soon awakened with the salty smell of the ocean surrounding the severe scent of herring at the fish shop. The anticipation of the slimy, silvery slice of herring about to touch my lips, followed by the terribly squishy and pungently salty sensation in my mouth caused an incredible burst of the senses. It seemed the whole world was welling up inside me. Then marching up the dune, the huge levee that protects the Dutch soil, the manipulative swelling of earth that demands the massive force of land from the seaand then to see the beach and the water on the other side. Nothing what I expected, but just like home, the sand under my toes and the new anticipation of the water splashing on my ankles. The smell of the air, and the sound of the water—so much piled upon the lingering thoughts of Susanna and the herring still at the tip of my tongue. I lost it.

This was just one of many intensely felt experiences of the past month. There have been so many moments that I feel such a desire to articulate and share with the world: playing hide and seek late into the night in the gardens in Giverny, running through Monet’s gardens in the pouring rain, losing consciousness beneath The Jewish Bride at the Rijksmuseum, herding the sheep at Coughton Court, and now laying in the grass atop a sunset illuminated hill in Stratford. We have been doing and seeing so much; some mornings I find myself waking up before four, unable to go back to sleep with ecstatic anticipation for the day to begin. With so much excitement around me I have never been more irritated with my body’s insensitive need to rest each night. Yet occasionally my inability to express and share this excitement makes me feel isolated and trapped within my own body. I am now realizing that the point of us all being here is simply to absorb, and see how everything affects each of us, in such a diversely creative collective, differently. We run through the houses of Shakespeare’s family not to understand how a specific fireplace might have influenced one of his plays, but to expose us to part of his context—to give us the opportunity to let it affect us, and our work in a different way than it did for him. To look at things that Rembrandt looked at, and see them in a very different way than he did, through ourselves, and what we already know and come from. Isn’t that what Rembrandt and Shakespeare did? Shakespeare knew other versions of the story of Lear, but he made King Lear his own by taking in the previous stories, along with everything else he knew and then breathing it all back out. Maybe Rembrandt didn’t copy the masters either, but instead looked at them and took them within himself before letting them inspire him and flow through him onto the page. I need to let everything I see flow through me without worrying about how to make everyone understand what I mean. If I let go, then anyone could take part of what I mean in a different way than I had even thought of it, enriching my experiences and making them live on. If someone reads this and goes to the beach at The Hague, they won’t experience it the way I did, but they will have added my experience to their collective perceptions. They will have their own mental picture of what it looked like the day that I was there, what it smelled like and felt like for me, and somehow that may affect the way they experience it themselves.

I think that I now understand what Pete meant yesterday when he said that he doesn’t paint from life, or from what he sees, but that he soaks in everything into his mind and paints from there. I guess that’s what we all do, whether or not we think about it in that way.

Two

When you look at something, your eye and the object are together, but exist in different contexts; they meet together to create the reality that we see. With a painting, another layer of contextual element is added—the artist. Here the layers of perception are multifaceted between the object (landscape, inspiration, etc.), the artist, the painting and the viewer, allowing him to bring forth his own interpretation. The difference between looking at Mt. St. Victoire and Cezanne’s painting of it is the element of Cezanne, his perception of the landscape, selection of what to paint and what to leave out, and his purpose in painting it. My viewing of the mountain will always be different than my viewing of Cezanne’s painting of it. The viewer who has seen the natural landscape of the mountain will view the painting in a different way than the viewer who has no previous context of what Cezanne might have seen—or for that matter, their own context of what they saw. In looking at Cezanne’s painting after having looked at Mt. St. Victoire, the viewer brings his own baggage, his own perception of his knowledge of what the mountain looked like to him. Similarly, in looking at the mountain, those who have previously seen Cezanne’s paintings will look at it with a different perception than those who have not.

Our own accumulation of visual knowledge is brought to each new thing that passes before our eyes. When I look at something, knowledge of things that I have previously seen stream through my head whether or not I am intentionally calling them forth. This is part of the reason why two people can look at the same object or image from the same angle and still see very different things. In a single image, different motifs are aroused for different viewers, and even those specific details within a motif appear different to each viewer. If everything that we see is different, then we will also represent everything differently. And further, we will respond differently to each representation; two people viewing the same painting of a landscape produce very different descriptions or responses to it. I was always so intrigued by Van Gogh’s remarks on his Night Café saying that, “I have tried to express with red and green the terrible passions of human nature,” because I never would have thought of red and green as such. The work of art is the collision between the artist and the viewer at a central spot. There is no one viewing or one interpretation of a picture because all of the circumstances around it constantly change its context and shed different light on it.

When I paint a tree, do I push myself upon it, or do I listen to what the tree tells me? Both seem to produce the same effect, yet create different meaning for the picture. If I paint a tree that looks sad to me, have I done so because I feel sad, or because I saw sadness within the tree? Or are both the same because I am seeing sadness in the tree only because I myself am sad? Either way, I have painted what the tree offered to me, which was filtered through myself and onto the canvas. While we all perceive the tree differently, each of our perceptions physically exists within the tree. Each person sees and perceives things differently each time they look at something due to infinite external and internal variables. Yet all of the different aspects that are perceived always physically exist within the object. Cezanne said, “Nature is on the inside,” because it is within us that nature is perceived as we define it. Jackson Pollock also believed that man was not separate from nature, but a part of it. He made this clear when Hans Hoffman was giving him a hard time for not working from nature, and Pollock famously retorted, “I am nature.” How can we separate ourselves from our surroundings? Where does the boundary between “interiority” and “exteriority” exist?

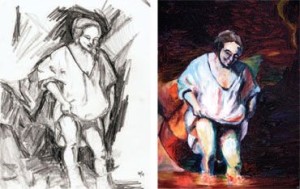

How does the subject matter affect how I approach a painting? When I painted a Rembrandt self-portrait, there were layers of perception in between Rembrandt’s presentation of himself and my interpretation and expression of what I saw in that. Although that seems like a more complicated interaction, it is the self-portrait I paint of myself from the mirror that is more complex. Representing Rembrandt as I see his presentation of himself is a much simpler feat than representing myself as I see myself. I am always changing and moving and thinking, while in this situation, Rembrandt is a moment stuck on a flat canvas.

Every time I try to create a self-portrait I start with a smile on my face. Yet as I develop my painting, my face becomes more and more intense until all of my self-portraits end up looking like I’m “stone cold evil,” as Leonard so thoughtfully remarked. In an attempt to conquer this, I did a painting from a photograph of my sister (the next closest thing to myself) and me very young, an abstracted moment in time that I no longer remember. I found this to be more like painting from Rembrandt than painting from the mirror, even though I knew the subject matter so well. I felt freer painting something that I am not physically attached to, like I have less of an obligation to the photograph than I do to myself in the mirror (Also the photograph does not move like me!).

The world is always as you see it, so you are always at the center of your own universe. Denying this in search for a universal view is false, and yet sometimes the most specific and personal statements have universal aspects to them. With painting we have a combination of two individual perceptions (the artist’s perception of his subject, and the viewer’s perception of the work). Talking about paintings, or natural landscapes that we see, is beneficial because we all bring together the different things that we see. We share our different visual experiences to broaden each of our visual knowledge and enhance our visual vocabulary. We must, however, do so with the overall understanding that no matter how much we try to articulate, describe and analyze each other’s visual experiences in words—they are visual experiences that are largely impossible to verbally articulate. The translation from visual motif to verbal language is never going to be a straightforward translation, just as the translation of 17th century Dutch into 21st century English is never exact. The intense discussion on Rembrandt’s intended meaning of the phrase ‘die meeste ende die naeteureelste beweechgelickheijt’ lends an interesting example. In a letter to Constantijn Huygens, Rembrandt claimed the Passion series was delayed in its execution because of the careful time he took to capture the ‘beweechgelickheijt’, which is perceived as meaning either motion or emotion. The ambiguous nature of the Dutch word significantly changes our perception of Rembrandt’s intention and creative process—but knowing his intended meaning of the word does not alter a single visual element on the canvas.

A painting is a concrete and tangible object that exists in physical space—yet it is simultaneously alive and communicating between the artist and the viewer.

Is the relationship between the natural landscape and the viewer a more mutual one than that between a landscape painting and its viewer? If so, maybe it is because with the painting you are looking at the aspects of the landscape that spoke to the painter, which are not necessarily the same ones that would have spoken to you if you were looking directly at the landscape. Looking at the painting can then be more illuminating than looking at the landscape, provided it opens up different things to look at that you would not necessarily have seen in the landscape. But a painting can also close up on you, being a secret world of the artist to which the viewer is not provided an open access. This is the mystery of art—its lack of direct straightforwardness. We can look at a landscape and describe what the landscape offers us, but we cannot look at a landscape painting and clearly describe what the landscape offered the painter. Jerry Saltz put it well when he compared art to a cat; you call the cat toward you and it looks at you and it looks away and it looks at you again and then as it is looking at you, it walks right past you to something else. A direct connection is not possible because there are layers of contexts (subject, artist, painting, viewer). Art will never be that simple, it will never walk up to you and jump in your arms telling you what it’s all about, and that’s why I love it.

Is the relationship between the natural landscape and the viewer a more mutual one than that between a landscape painting and its viewer? If so, maybe it is because with the painting you are looking at the aspects of the landscape that spoke to the painter, which are not necessarily the same ones that would have spoken to you if you were looking directly at the landscape. Looking at the painting can then be more illuminating than looking at the landscape, provided it opens up different things to look at that you would not necessarily have seen in the landscape. But a painting can also close up on you, being a secret world of the artist to which the viewer is not provided an open access. This is the mystery of art—its lack of direct straightforwardness. We can look at a landscape and describe what the landscape offers us, but we cannot look at a landscape painting and clearly describe what the landscape offered the painter. Jerry Saltz put it well when he compared art to a cat; you call the cat toward you and it looks at you and it looks away and it looks at you again and then as it is looking at you, it walks right past you to something else. A direct connection is not possible because there are layers of contexts (subject, artist, painting, viewer). Art will never be that simple, it will never walk up to you and jump in your arms telling you what it’s all about, and that’s why I love it.

Three

With Edgar’s closing remarks in King Lear being, “The weight of this sad time we must obey, Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say (3.3.322),” he lays the weight of the tragedy on the tension between feeling and duty. Cordelia and Kent, both being banished for speaking as they “felt,” are juxtaposed to Goneril and Regan, whose words from the start are carefully composed, as they “ought” to be. However, it seems the root of the tragedy actually lies in Cordelia’s not speaking, as she ought, for if she had composed something more than “Nothing,” as her sisters had, the following events would not have unfolded in such a manner. Edgar has proven his poor judgment through the ease with which his brother manipulated his actions; are we to believe that his words here are misjudged as well?

It is difficult to clarify the difference between speaking what we feel and what we ought without a specific context. This is because it is often the case that in order to be honest we often ought to speak as we feel, and it is simple to blend the two together. During the opening scene of King Lear, Cordelia speaks as she ought and as she feels, but only after her initial stuttering of “Nothing”—which was neither what she felt nor as she ought to speak. Goneril and Regan spoke as they ought, perhaps fudging how they actually felt, but to no harm for Lear. In the case of the love test, speaking truly to how one felt was more harmful than speaking, as one ought.

Duty and obligation also change with the passage of time. In King Lear, there is a constant confusion and muddling of this because of an inability to internally incorporate exterior changes. Although Lear gives away all of his power to Cornwall and Albany, he strives to hold on to “The name, and all th’addition to a king (1.1.136).” Lear’s inability to internalize the external changes around him, as he attempts to hold on to his kingly persona, impact his tragic end greatly. The argument between Lear and Goneril over him keeping his one hundred-knight entourage, though they are loud and boisterous, lends example to his own impact on his downfall through his inability to incorporate exterior changes such as living with Goneril.

Rembrandt’s multiple-state print series have a temporal quality similar to theater. The tension between feeling and duty can be seen in the evolution of states in Rembrandt’s Three Crosses, which display an acceptance in the changes in duty caused by internal changes in his feelings. Rembrandt seems to begin, as he “ought” to, with a more conventional perception and portrayal of the story through Christ’s salvation. Here Christ is clearly being saved as his body is enveloped in the divine light that floods down from above. The development of Rembrandt’s later stages could reflect his own feelings and interpretations of the subject. His personal doubt in the salvation seems to be reflected in the muddling of the divine light, which is so clearly seen in the earlier state, and the harsh and somewhat chaotic lines through the other crucified figures. The later states of the print possess a greater confusion particularly of light—they seem to represent Rembrandt’s own confusion with the story. The external light source and external hierarchy of the early states evolves into an internal light source with an adherence to personal feelings on the subject rather than conventional interpretation. The Three Crosses starts as a dutiful representation of the salvation aspect of the crucifixion story and evolves into a representation of the confusing nature of the subject. If this is a temporal presentation of Rembrandt’s thoughts on his subject then he is reworking the plate, as he “ought,” by remaining true to himself, and his own perception of the subject. Here is a merging of feeling and duty as Rembrandt’s duty as an artist is to represent his feeling and interpretation of his subject.

With Rembrandt’s series of Christ Presented to the People, he again shows the process of working through his ideas by reworking the surface of his plate over time. The sequential depictions in this series have a particularly theatrical quality with their adding and removing of figures. In the beginning there is a group before Christ, and as the viewer we are watching them do the judging. But in the later states they are more removed and it is the viewer who is judging Christ. Then, in the latest states a murky foreground is developed with a statuesque central figure. In the Metropolitan print room we were able to look at several states of this series. It was really beneficial to see them side by side—looking back and forth from one to the next, taking note of each change that he made. However, I have to question whether this was Rembrandt’s intention. In signing only the later states of these series, it seems that he didn’t think the earlier ones were developed to his satisfaction, and that it was the later ones that expressed his interpretation of the subject. The theatrical quality of seeing them lined up next to one another, as if sketches of different acts in a play, was quite an invigorating experience.

Rembrandt’s earlier painting of Abraham and Isaac is aggressive and brutal, the figures are separate and there is a violent force running between them. The later etching of the same subject highly contrasts its earlier counterpart. Here the three characters are one as the angel envelops them together. Rather than portraying the divine as external and coming from above the figures, the divine light emanates from within the page. Rembrandt focuses onAbraham’s confusion as can be seen in his eyes, which are vacant and blank. While the physical connection of the figures is emphasized, their individual lines of vision are scattered. Their external connection contradicts their emotional separation and implies that their interiorities are separated and lost. Perhaps Rembrandt sees the confusing redundancy of the story and of Abraham’s situation. Why does god tell Abraham to go sacrifice if he intended to halt the sacrifice at the last minute? Wouldn’t this be a moment of despair and inner turmoil? If Abraham’s eyes are blank to indicate his blind faith in God then why does he look so sad? Wouldn’t Abraham’s blind faith in God take away his own interiority and leave him a soulless puppet, ready to sacrifice his son and then stop at the very last minute? The story opens questions, and it seems that in his later depiction Rembrandt leaves those questions open-ended. He does not attempt to define what it happening in this scene, but instead expresses it as completely as he can comprehend it.

There is also an intentional confusion of anatomies; as the angel embraces Abraham to stop him, her arms seem confused with his as one is extremely foreshortened. In our discussion of this print we spent some time deciphering whose hand is whose, making sure we were all in united understanding. I found this quite interesting considering the opposing forces of each hand. The function of Abraham’s hands are to kill his son, while the angels’ hands are present for the sole purpose of stoppingAbraham’s, so why is it so difficult to tell whose is whose? Each hand is specific and different from the rest. The angel’s right hand is significantly larger than his left, as though each hand knows its purpose and exists alone—detached from its body and from the surrounding hands.

Abraham turns in to hear, but not toward the angel; it is as if he listens to something else. He also does not seem to be grabbed from behind, by the angel, but grabbed from within himself. At this moment when the angel has appeared to stop him, he should be shocked, relieved, overwhelmed, but he is none of these. Abraham seems as though displaced from his own body and existing somewhere else in his mind. This is why the light comes from within, and whyAbraham does not look shocked at the angel’s sudden presence, grabbing him. He heaves a sigh within himself, as if he is internally lost.

Are these later depictions reflecting an older man’s spiritual confusion? The exterior clarity in the earlier works opposes the interior confusion of the later states. The earlier works are defined by the action, which is purposefully confused and distorted in the later works as Rembrandt reflects on complications within the stories. The confusion of the later states seems more honest, as he put more of himself into the works. The reworkings show Rembrandt’s thought process and internalization of the scenes and stories he represented, as though he created them in order to comprehend the stories. Rembrandt embraces the mystery of his subject as he admits a lack of complete understanding in the stories.

Four

In cutting open the lemon, it became apparent how the interior and the exterior affected each other. As the lemon aged this became more emphasized, as the interior seeped out to alter the exterior. Where the pulp lines divided the interior of the lemon, the exterior buckled slightly. The interior all broke down into sections, the organized skin dividers broke the lemons pulp into eight groups, and within those little sanctuaries the individual pulps resided, and they probably broke down into even smaller divisions within themselves. Where does interiority exist if exterior forces constantly affect it? Is interiority in fact an individual’s perception, interpretation and internalization of exterior forces? Our interiority only exists for one moment before it changes. Or are we constantly developing entirely new interiorities?

In cutting open the lemon, it became apparent how the interior and the exterior affected each other. As the lemon aged this became more emphasized, as the interior seeped out to alter the exterior. Where the pulp lines divided the interior of the lemon, the exterior buckled slightly. The interior all broke down into sections, the organized skin dividers broke the lemons pulp into eight groups, and within those little sanctuaries the individual pulps resided, and they probably broke down into even smaller divisions within themselves. Where does interiority exist if exterior forces constantly affect it? Is interiority in fact an individual’s perception, interpretation and internalization of exterior forces? Our interiority only exists for one moment before it changes. Or are we constantly developing entirely new interiorities?

Seeing the Wilton diptych in the National Gallery reminded me of some of my thoughts on interiority from early on in the trip. There is a separation of worlds on the interiors of its two panels—one being heaven and the other the earthly sphere of Richard II. There are layers of interior space, with two sides, an inside and an outside. The mystery of the interior is emphasized with the diptych format as the exterior contrasts the interior and can close up to hide what is on the inside.

Interiority is not directly articulable because it is different for all. Not only do we have immense difficulty articulating our own interiority, we have struggled to even articulate a concise definition of the word interiority. It is not possible for it to be cleanly, or perfectly, translated from one person to another because two people have different interiors. Yet, with Rembrandt and Shakespeare interiority is expressed in an indirect way, through art. We cannot know if Rembrandt or Shakespeare intended their art to reflect their interiorities, but nonetheless aspects of it seep out indirectly. Looking at a Rembrandt self-portrait, he is dressed in costume and presenting himself in a certain way for the viewerbut something else is captured. His two eyes never match perfectly, as when painting yourself, one eye is always looking back and forth between the mirror and the painting. They are distinct from one another and give different information. Or is it a purposefully ambiguous presentation to confuse the viewer, and not reveal the “true” Rembrandt.

With both soliloquy and self-portrait we have a supposed presentation of the interiority of a character, which we perceive as real or honest because of the nature of the media. Of course soliloquy and self-portraiture have the capacity to fool us more than any other media. Each manipulates our perceptions of the character by making us feel they are divulging a secret only to us. More can be learned about a person’s character in watching their interactions than by interpreting their concocted presentation of themselves. You can understand more about someone’s personality from watching them talk to their friends than by listening to them analyze themselves to a psychiatrist. Yet, if we read beyond a character’s words, and into their tone, secrets can get out. It’s also like what Matisse said about expression existing within the formal elements of a portrait—the color and the line, not within the face.

With Rembrandt’s portraits of others, for example of Nicolaes Ruts, there is a layered interpretation of interiorities. Ruts presents himself to Rembrandt as he wishes to be depicted, and from that Rembrandt’s own interior perceives different aspects of Ruts that were presented. Rembrandt will relate what he sees, or what he thinks, about Ruts to things that he has already seen and known. From this Rembrandt will present aspects of his interpretation of Ruts. The viewer then, being Ruts’ family looking at the picture contemporary to its creation or us looking at him 400 years later in the Frick Collection, looks at the picture with their own interiority. He brings his own interpretation perceived from personal and visual knowledge. All of these layers collide together within and without the painting, lending every viewing of it to be different. This intersection of interiorities creates an entirely new one.

Plays have two-fold possibilities; we can internalize them by reading, or externalize them by watching. It’s overwhelming to think about all the specific decisions that a director makes that decide our perception of the play. By showing Banquo’s ghost on stage in Macbeth, we relate to his character more than the others because we see what he sees. Or by playing out the rambunctious nature of Lear’s entourage we sympathize with Goneril’s decision to throw them out. When I am reading a play, I might see all of these possibilities in an open-ended fashion, or I might only see it one way and not even be aware of other dramatic interpretations that could be portrayed. That is what is so incredible about Shakespeare’s plays, and theater in general. King Lear has been performed countless times for hundreds of years and yet it has never and will never be performed exactly as I saw it performed in my head when I first read it.

In one of our initial lectures on King Lear, Dr. Mitova said that she had never seen a satisfying performance of King Lear, that the polydimensionality of our imagination can never be fully conveyed. When something is put on stage, decisions of inclusion and exclusion must be made that do not have to be made while reading the text. That is why the plays continue to be performed. Performing Shakespeare is like a continuous search for the initial high of reading the play—but it will never be reached. Watching the plays is illuminating when it brings forth ideas in the text that I had not yet thought of, but it can also be ultimately disappointing when actions don’t unfold with the epic force that they do in my head.

Theater is intangible, nothing is fixed, and everything is constantly changing. Although this is like the act of drawing or painting, the final product of a drawing or a painting is fixed and unchanging. It was interesting to look at the opposite of this, the still photographs from RSC productions. These images were exciting in themselves, but static. I found myself thinking of the subject as a single image, and not as part of a series of images that existed within the context of a play, it was interesting then to learn that they are in fact staged and photographed individually and not during a live production. In this way theater is most like the act of painting. Theater is more lucid as a search, an act that is constantly evolving, rather than as a finished product. But painting also is about the finished product. I would never look at a painting of Mt. St. Victoire and think, “Gee, I really wish Cezanne had included that yellow tree.” But, I might wish for changes even in a really good Shakespeare performance, and I think that is the nature of the media.

Rembrandt keeps us reminded that we are looking at a painting with the thick intensity of his brushstroke, while Shakespeare keeps us reminded that we are watching a play (or reading one) by the guiding speeches. The context of our own interior space also does this; we know we are looking at a painting because of its context within the museum, and we know that we are watching a play because of its context within the theater. The interiority of the space affects the way that we perceive its inhabitants. It is an incredible phenomenon to be in a dark theater, surrounded by a mass of people all intently observing the same dramatic scenario—when these same people might walk right by drama unfolding on the street, or in their home, all day long. Within a museum as well, exists a structure with the specific purpose of having people look closely at things. We need that layer of detachment to arouse our manipulated feelings—with painting and with acting. We need to know that it is a painting or that this person is acting, and is presenting to us an interiority different than their own. A long time ago an actor told me that because he smoked cigarettes in real life, when he had to in a show he wouldn’t inhale—otherwise he would forget he was acting. Now I understand what he meant.

As an actress, the character of Cordelia must capture an inability to articulate her interiority (inner thoughts, emotions, feelings) to her father during the love test. Those acting the parts of Goneril and Regan, who must speak in a manner that express a false interiority, contrast her role. They must successfully articulate their love in a way that fools their father into thinking that they speak truthfully, from the heart, and that directs the audience to the falsity of their speeches. Cordelia’s side remarks struggling with the feat of speaking her heart through her tongue help emphasize Goneril and Regan’s false nature to the audience. However, these lines were cut in the production we saw in Stratford and instead the comical nature of the staged quality of the scene was emphasized. Goneril and Regan were clearly portrayed enacting prepared speeches and not speaking from the heart. Actors need to search for the inner motives of the character, to understand why it is that they say and do these things—to successfully project the character to the audience.

Edmund is one of the few characters in King Lear who sees that people have interiority and are not just vessels enclosing roles. He goes beyond artificial distinctions to protest that he is not just a bastard. Delighting in all levels of human interiority is something that both Rembrandt and Shakespeare do. By depicting everyone from kings to commoners, they both break the superiority complex by individualizing representations of all. Shakespeare puts interiority into even the anonymous “Murderer 1” in Macbeth, who speaks insightfully on Banquo’s approach and anticipates his desire for the inn and it’s provided rest (3.3.5). Rembrandt’s etching Self-Portrait as a Beggar shows him playing roles with himself, using his body to discover different interiorities. He studies other people by projecting himself into them. Instead of going to Italy to study, he studies his own Dutch interior and the people.

Shakespeare also plays with the effects of disguise. Interiority can be moved, like a snail from one shell to another, but it must re-shape to fit its new home. It is when Edgar says, “Poor Turlygod, poor Tom, That’s something yet: Edgar I nothing am, (2.2.191)” that he begins to reveal himself. Edgar’s interior worth strengthens as his exterior worth weakens, as a mad beggar. Edgar, as well as Kent, disguises himself on the exterior to reveal a truth about his interior; a change in exteriority allows for a revelation of interiority. In his disguised exterior, Kent is able to speak as he feels to the King. With these characters we see the strength of the exterior presence, and the effect it has. In the production we saw of King Lear, on the other hand, the strength of Lear’s kingly presence was just as strong when he was naked in the storm as it was in all his ceremonial regalia at the play’s opening.

The most appalling aspect of King Lear is that Lear’s downfall, and the tragedy of the story, came from within his interior. Goneril, Regan and Cordelia came from him, and are made from what is inside him, and it is their actions that destroy him. So really, it is he that destroys himself. Lear says to Goneril, “But though art my flesh, my blood, my daughter, or rather a disease that is in my flesh, which I must needs call mine. Thou art a boil, a plague-sore, or embossed carbuncle in my corrupted blood. (2.4.335)” This is one part of the play that I can visually imagine very clearly. There are these creatures coming out of Lear’s diseased yet arrogant body, and they are tearing at his flesh, and binding up his eyes and mouth, and ripping at the crown that is physically attached to Lear. The disease that ruined Lear wasn’t just his daughters, it was he himself.

In the version of Macbeth that we saw in Stratford this was played up as well. By having Macbeth savagely killing the babies of the witches in the first scene, it is apparent that Macbeth’s own actions are what destroyed him. The witches are not this exterior force of nature that randomly comes along to initiate Macbeth’s actions; they come from within him—within his own nature. That is the shattering truth that we must take responsibility for if we are to take to heart Cezanne’s insightful words: “Nature is on the inside.” The most catastrophic aspect of our tragedy is realizing that we are responsible for it.

Five

When the trip first ended I thought it was really upsetting. I had done and seen all of these amazing things with such interesting and insightful people, and then suddenly I was in Delaware—alone in my parent’s garage trying to think about everything I had just experienced, how we had gone so many places and seen so many things. And then as I started to think about Rembrandt and Shakespeare it dawned on me that our focus was on two artists whose homes had more of an impact on them than anything else. We studied Shakespeare through his home of Stratford, and Rembrandt who never left his Dutch home in search of Italy, as so many of his contemporaries did. And I realized that while this trip has left me with such a yearning to keep traveling to see new things, it has also left me with a delightful contentment for my immediate surroundings. I have a new appreciation for how the everyday world around me affects and inspires me. The despair of no longer being able to look out my bedroom window ontoMonet’s gardens, has been overcome by an excitement in looking out my window each morning to luscious cornfields at the peak of their season. A view newly awakened by my senses.

As I sit here, cleaning up my messy sentences and organizing my images, Alan and John’s words are echoing through my head, “Kill your internal editor.” Although I have recently gained a certain amount of trust in my self-expression, having this journal published can’t help but make me feel as though I am standing in the street naked waiting for people to poke at me. I couldn’t feel more vulnerable if my journal included twenty nude self-portraits with accompanying verbal descriptions—because really this is the same thing. Yet my senses are tickled with this vulnerability.